Can common nutrients curb violent tendencies

and dispel clinical depression?

DISCOVER Vol. 26 No. 05 | May 2005 | Biology

& Medicine

|

Mental

Machinery

|

When pigs are

penned in close quarters, some become so irritable they savage

their pen mates’ ears and tails, a problem farmers call

ear-and-tail-biting syndrome. David Hardy, a Canadian hog-feed

salesman from the farmlands of southern Alberta, knew

that behavior well. Years of experience had taught him

something else: All it takes to calm disturbed pigs down is a

good dose of vitamins and minerals in their feed.

That

came to Hardy’s mind one November evening in 1995 when an

acquaintance, Tony Stephan, began confiding his troubles. His

wife, Deborah, had killed herself the year before after

struggling with manic depression and losing her father to

suicide. Now two of his 10 children seemed headed down the

same road: Twenty-two-year-old Autumn was in a psychiatric

hospital and 15-year-old Joseph had become angry and

aggressive. He had been diagnosed as bipolar, a term for manic

depression, but even with medication he was prone to outbursts

so violent that the rest of the family feared for their

lives.

The

boy’s irritability sounded familiar to Hardy. I don’t know a

whole lot about mental illness, Hardy told Stephan, but I’ve

seen similar behavior in the hog barn, and it’s easy to

cure.

So the

two men set out to create a human version of Hardy’s pig

formula. They bought bottles of vitamins and minerals from

local health-food stores and spent nights at Stephan’s kitchen

table concocting a mixture. On January

20, 1996, they

gave Joseph the first bitter-tasting dose. Within a few days,

Joseph felt better than he had in months. After 30 days, all

the symptoms of his illness were gone.

Stephan

next turned to Autumn, whose mental state had been steadily

deteriorating for years. Now she was psychotic, convinced she

had a gaping hole in her chest from which demons emerged. Just

released from the hospital where she’d been on suicide watch,

Autumn required 24-hour supervision to ensure she didn’t hurt

either herself or her 3-year-old son.

Stephan

forced her to take the nutritional formula. After just two

days of treatment, her rapid swings between mania and

depression stopped. After four days her hallucinations

vanished. “I remember saying, ‘Oh my gosh, my hole is gone,’ ”

she recalls. By week’s end, she felt well enough to quit all

but one of her five medications.

Nine

years later, both Autumn and Joseph remain symptom free,

medication free, and devoted to taking what they call “the

nutrients” each day. Autumn Stringam, her married name, is an

articulate woman with bright eyes who revels in being a

full-time mother to her son and the three daughters she’s had

since getting well. “I don’t feel I’m cured,” she says. “I

feel I’ve got something that allows me to manage and have a

normal, functional life—maybe even better than

functional.”

It’s

easy to write off the Stephans’ treatment as just one more

crackpot cure in a field rife with fraud and false hope. The

supplement they took has yet to be proved in large clinical

trials, while scientists who have studied it have been caught

in the cross fire between converts, willing to take the

supplement on faith and anecdotal evidence alone, and skeptics

who look askance at all alternative medicine. Yet the idea of

treating mental disorders with supplements makes sense,

experts in the field say. Micronutrients help build and

sustain the brain’s architecture and fuel its biochemistry.

They are critical in countless ways to the working of cells

throughout the body, including the brain. “We need 40

essential micronutrients in our diet—vitamins, minerals, and

essential fatty acids,” says Bruce Ames, a biochemist at the

Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute. Ames has

explored the impact of zinc and iron on brain cells. “If you

don’t have enough of one, you’re fouling up your

biochemistry.”

A

number of diseases caused by nutrient deficiency, such as

scurvy, beriberi, pellagra, and pernicious anemia, display

psychiatric symptoms like irritability and depression. But

while severe deficiencies are rare in the developed

world—when’s the last time you met someone with beriberi?—many

of us fall short of getting all the nutrients we need. In 1997

a British study compared the mineral content of fruits and

vegetables grown in the 1930s with the mineral content of

produce grown in the 1980s. It found that several nutrients

had dropped dramatically, including calcium (down nearly 30

percent), iron (down 32 percent), and magnesium (down 21

percent).

Some

researchers suspect that even mild deficiencies can affect the

psyche long before any physical symptoms appear. Stephen

Schoenthaler, a sociologist at California

State

University at

Stanislaus, has been exploring the link between nutrients and

mental health by giving basic vitamin and mineral supplements

to prison inmates and juvenile detainees. Again and again,

since the early 1980s, Schoenthaler has found that when inmate

nutrition improves, the number of fights, infractions, and

other antisocial behavior drops by about 40 percent. In each

case, he has found, the calmer atmosphere can be traced to the

mellower moods of just a few hotheads. The inmates most likely

to throw a punch, he has discovered, are the ones with the

least nutritious diets and the lowest levels of critical

nutrients.

Schoenthaler’s

findings have been undermined by less than sterling research

methods: His papers have failed to describe the precise

methods by which he analyzed the inmates’ blood. (In January,

a committee at his university recommended that he be suspended

for a semester without pay for academic and scientific

misconduct in later, unrelated research.) So in the late

1990s, an Oxford

University

physiologist named Bernard Gesch decided to put the theories

to a more rigorous test. Gesch divided 231 prisoners in one of

Britain’s

toughest prisons into two groups. Half were given a standard

vitamin and mineral supplement each day as well as fish-oil

capsules and omega-6 oil from evening primrose. The other half

received placebos. The results, published in 2002 in The

British Journal of Psychiatry, drew headlines on both

sides of the Atlantic. They

were also almost identical to Schoenthaler’s. Over the course

of approximately nine months, inmates taking supplements

committed about 35 percent fewer antisocial acts than the

group taking placebos. A few weeks after the study started,

the prison warden told Gesch that the administrative report

that month showed no violent incidents had occurred. “As far

as he was aware, this had never happened in the history of the

institution,” Gesch says.

Poor Man’s Pharmacopoeia

A

number of common nutrients may help alleviate mental illness

when taken in higher-than-normal doses. A few of the most

promising candidates follow.

FOLIC

ACID

Folic acid is a B vitamin essential to mood

regulation and the development of the nervous system. Patients

deficient in it appear to respond poorly to antidepressants.

In one 2000 British study, 127 patients taking Prozac were

also given either 500 micrograms of folic acid a day or a

placebo. The folic acid group did significantly better, in

particular the women, 94 percent of whom improved compared

with 61 percent in the placebo group.

MAGNESIUM

It’s long been

known that magnesium can act as a sedative. Some studies have

also found magnesium deficiencies in patients with depression,

although the evidence is inconsistent. The mineral may help

other mood-stabilizing drugs work better. Researchers at the

Chemical Abuse Centers in Boardman,

Ohio, found that

combining magnesium oxide with the drug verapamil helped

control manic symptoms in patients better than a drug-placebo

combination.

CHROMIUM

Several studies

have suggested that chromium picolinate may help alleviate

depression and improve the response to antidepressants. In one

small trial at Duke

University, 70 percent of

the patients who were given chromium picolinate improved,

while none of those given placebos got

better.

INOSITOL

This sugar molecule appears

to make the brain’s receptors more sensitive to serotonin, one

of the chemical messengers that mediate mood. In a series of

short-term placebo-controlled trials, researchers at Ben

Gurion University of the Negev in Israel found that large

doses of inositol—12 to 18 grams a day—helped alleviate

depression, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive

disorder.

The

study of micronutrients and mental health is known as

orthomolecular psychiatry, a term coined by two-time Nobel

laureate Linus Pauling in a controversial 1968 essay. Pauling

wrote that nutritional supplements, unlike psychotherapy or

drugs, represent a way to provide “the optimum molecular

environment for the mind.” Varying the concentrations of

substances normally present in the human body, he wrote, may

control mental disease even better than conventional

treatments.

|

A

|

|

B

Micrographs courtesy

of Celeste Halliwell

|

Today

the Society for Orthomolecular Health Medicine counts about

200 American members. One of the foremost practitioners, the

Canadian psychiatrist Abram Hoffer, claims to have

successfully treated thousands of schizophrenics with massive

doses of vitamin C and niacin. He contends the vitamins

neutralize an oxidized compound that causes hallucinations

when it accumulates in the brains of patients. Until recently,

such treatments thrived on the power of patient lore, not

scientific certainty. Nutritional therapists were generally

unwilling to test their claims in well-designed controlled

studies. “Even when studies were done, they just didn’t meet

the standards of rigor that would make them be taken

seriously,” says Charles Popper, a Harvard

University

psychopharmacologist who studies bipolar disorder.

In

1973 a task force of the American Psychiatric Association

issued a withering indictment of orthomolecular psychiatry,

concluding that “the credibility of the megavitamin proponents

is low.” For the next two decades, funding for orthomolecular

research was rare. Academia turned its back on the field, and

industry saw no profit in it—vitamins and minerals can’t be

patented like other medicines. In recent years, however,

grants from the National

Center for

Complementary and Alternative Medicine, founded in 1998, and

new discoveries in brain biochemistry have prompted

researchers to take a second look at nutritional therapies.

The strongest evidence to date involves omega-3 fatty acids, a

group of compounds abundant in fish oil of the kind Gesch gave

to prisoners, as well as in the membranes of and synapses

between brain cells. In a landmark 1999 study, Harvard

psychiatrist Andrew Stoll found that bipolar patients who were

given large doses of omega-3s did significantly better and

resisted relapse longer than a matched group of patients who

were given placebos.

Stoll’s

findings have yet to be replicated, but other researchers have

since studied omega-3s as a treatment for depression,

schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, and attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. (See “Fish Therapy,”

opposite page.) “In every case, the data has been

overwhelmingly positive,” Stoll says. Other research has shown

correlations between low levels of various nutrients—zinc,

calcium, magnesium, and B vitamins—and depression. Researchers

have found that anywhere from 15 percent to 38 percent of

psychiatric patients have reduced levels of folate. A 2000

study of older women found that 17 percent of those who were

mildly depressed and 27 percent of those suffering severe

depression were short on vitamin B12.

In an

effort to winnow out confounding variables, nutritional

research has long focused on single nutrients. Yet some

researchers, like Stoll, have suggested that the effects of

nutrients are additive—that their real strength becomes

apparent only in a multinutrient formula. A formula much like

the one that Tony Stephan and David Hardy first stumbled upon

in a hog barn.

|

FISH THERAPY

Omega-3s are a family of fatty acids found

in seafood and certain plants such as flax. Researchers

are interested in their therapeutic potential for

several reasons: Large population studies have shown a

correlation between rates of seafood consumption and

depression. Small studies have found patients with

depression have reduced levels of these fatty acids in

their blood. A variety of small clinical trials have

also suggested that omega-3s (at doses ranging from one

to four grams) may alleviate the symptoms of depression,

schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, as well as improve

patients’ response to conventional medicines.

Some researchers speculate that fatty

acids help maintain fluidity in the cellular membranes,

allowing neural receptors to better detect incoming

signals. Others, like Harvard psychiatrist Andrew Stoll,

believe that omega-3s affect the brain in ways similar

to mood-stabilizing drugs like lithium and Depakote:

They tamp down excessive signaling between cells. Stoll

says the compounds also reduce cellular

inflammation—common in people with mental

disorders—stirred up by omega-6s, another family of

fatty acids. In centuries past, humans ate a great deal

of wild game, greens, and other foods rich in omega-3s.

Today we eat fewer omega-3s, while filling up on foods

heavy with processed vegetable oils, which are high in

omega-6s. The change may help account for the increased

incidence of depression in the past 100 years, Stoll

says.

Stoll’s colleagues say that the compounds

show promise but require further research. “The problem

is there’s not a lot of published evidence yet,” says

Harvard psychiatrist David Mischoulon. “So it’s hard to

compare this modest body of evidence against evidence

for a medication like Prozac or Zoloft that has numerous

studies to back it up.”

—S.F. |

After

Stephan and Hardy’s success, they spread word of the treatment

among fellow Mormons in southern Alberta. They

began by whipping up batches of the formula for church members

suffering all sorts of disorders, from mild depression to ADHD

to schizophrenia. Then, in early 1997, they quit their jobs

and began selling the formula, which they eventually named

EMPowerplus (the EM stands for “essential mineral”). Their

company, Truehope Nutritional Support, employs 35 people in a

squat building on the edge of Hardy’s hometown, the tiny farm

community of Raymond.

Stephan,

52, is stocky and energetic, with blondish-gray hair, earnest

blue eyes, and a nose that skews slightly to the right as if

it had been broken. Hardy, 55, is tall and lean, with square

wire-rimmed glasses. It’s not hard to see him as the high

school science teacher he once was. The two relate the story

of their supplement with a practiced air. Both are devout

Mormons who seem to believe they’ve been given a mission to

alleviate mental illness. Although the supplement is not

inexpensive—a month’s supply costs $69.98—Stephan and Hardy

say it is expensive to manufacture, and the business barely

turns a profit.

For

years, they say, they tinkered with the formula, using Autumn

as their guinea pig. “A lot of it was trial and error,”

Stephan says. “There’s nothing out there saying that if you’re

bipolar you need 50 milligrams of zinc.” The latest

incarnation of the supplement contains 36 vitamins, minerals,

amino acids, and antioxidants. Most are the same ingredients

found in a typical multivitamin but at much higher doses. For

example, a daily dose of the supplement contains a whopping

120 milligrams of vitamin E, six times the recommended daily

allowance. So far, the only side effects appear to be nausea

and diarrhea, but no one really knows the long-term dangers of

taking high vitamin and mineral doses.

News

of the supplement has spread quickly through the Internet and

patient support groups. Hardy says at least 6,000 people have

used the supplement for psychiatric problems, and a few

thousand more have tried it for other central nervous system

disorders such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease,

cerebral palsy, and stress. Like many alternative therapies,

the supplement has generated tales of dramatic results, but

Stephan and Hardy know that they need solid research to prove

its effects.

Several

years ago, they began contacting scientists, including Bonnie

Kaplan, a research psychologist at the University of

Calgary, and

Harvard’s Charles Popper, inviting them to study their

mixture. The scientists had essentially the same response. “I

told them to take their snake oils somewhere else,” as Kaplan

later recalled to a reporter. Popper was so leery of the pair

after his first meeting that he hid the bottle of the

supplement they gave him under his coat as he walked back to

his office: “I was afraid someone was going to see me with the

stuff.”

Kaplan

finally agreed to meet with Hardy and Stephan in 1996.

Impressed by their sincerity, she decided to offer the formula

to a handful of patients who had not responded to conventional

treatments. Kaplan first tried the supplement on two boys with

wildly shifting moods and explosive tempers. One was so

obsessed with violent fantasies that he could not go more than

20 seconds without thinking about guns. After he started

taking the supplement, Kaplan later wrote in a case study, his

obsessions and his explosive rage diminished. When he quit the

supplements, the obsessions and anger returned. Back on the

supplements again, the symptoms retreated.

Those

results were encouraging enough that within a few months

Kaplan started a small clinical study of 11 bipolar patients

who had not been able to control their illness with

conventional medications. After six months of treatment, each

of the 11 showed improvement in both their depression and

mania. Most were able to cut down on their medications, and

some quit using them altogether.

In

2000 Kaplan accompanied Hardy and Stephan to Harvard’s

McLean

Hospital to

talk with other scientists. Popper was skeptical, despite

Kaplan’s credentials. That night, however, he got a call from

a colleague whose son had suddenly developed bipolar disorder

and was throwing violent tantrums daily. Popper reluctantly

offered him the

sample bottle of the supplement that Hardy and Stephan had

given him, figuring it couldn’t hurt. He did not believe it

would help. Four days later, the father called to tell him the

tantrums were gone. “The kid wasn’t even irritable,” Popper

recalls. “We don’t have anything in psychiatry that can do

that.”

Like

Kaplan, Popper gradually began giving the formula to bipolar

patients who had not done well on psychotropic drugs. The

supplement not only worked for 80 percent of the patients, it

also took effect far more quickly than conventional drugs for

many of them. After testing the supplement for six months and

seeing improvements in some two dozen patients, Popper decided

he had something noteworthy enough to share with colleagues.

In 2001 he and Kaplan each published articles in The

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry describing their findings

and encouraging further research. “What if some psychiatric

patients could be treated with inexpensive vitamins and

minerals rather than expensive patented pharmaceuticals?”

Popper wrote. It was a strikingly optimistic statement about a

discredited idea. “I knew going public would raise a lot of

eyebrows, that I was putting my career on the line,” Popper

says. “But I was convinced.”

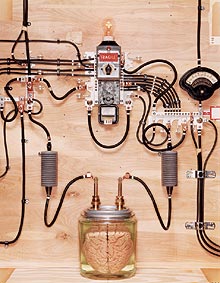

|

BRAIN

POWER

|

One

reason that orthomolecular psychiatry was treated with such

derision in the 1960s and early ’70s was that biologists had

only a faint understanding of the physical effects that

nutrients had on the brain. In the past two decades, however,

researchers have begun to gain a better understanding of the

brain’s biochemical machinery. Psychiatrists now know that

nutrients are the brain’s backstage crew, endlessly

constructing and maintaining cellular set designs, directing

players to their marks. They also play important roles in the

creation of chemical messengers thought to mediate mood, such

as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Zinc is a

particularly versatile player, involved in more than 300

enzymatic reactions; when zinc goes missing, a cell’s DNA and

its repair machinery can be damaged.

Neuroscientist

Bryan Kolb, at the Canadian Centre for Behavioural

Neuroscience in Lethbridge,

Alberta, has

explored how brain cells are affected by drugs, hormones, and

injury. When Stephan and Hardy first approached him in 1997,

he politely declined to start up a study. He had little

psychiatric expertise, he explained, and his usual

experimental subjects had four legs and long tails.

Two

years ago, Kolb decided to take another look. In an effort to

tease out a biochemical pathway that might account for the

clinical effects that Kaplan, Popper, and others had

described, he ran a series of rat studies. First, he inflicted

injuries in two parts of infant rats’ brains: the frontal

lobe, which controls motor function and the ability to plan

and execute tasks, and the parietal lobe, which influences

spatial functions. Half the group then got a diet spiked with

a supplement similar to EMPowerplus and half got plain rat

chow. When Kolb put them through a series of cognitive and

spatial-ability tests, the vitamin-charged rats did markedly

better than the control group.

Kolb

noticed something else about the supplement-fed rats: “They

were unbelievably calm.” Lab rats usually flinch and squeal

when identification tags are stapled onto their ears, he says.

“These rats acted like nothing had happened.” Kolb then

autopsied the rats’ brains: The formula-fed rats had bigger

brains than the chow-fed rats. In areas near where he’d

inflicted lesions, the dendrites of the existing cells—the

long, tentacled parts of neurons that conduct electrical

impulses—had sprouted new branches, each ending with hundreds

of new synapses. (In an earlier study, Kolb had found that the

amino acid choline could also stimulate dendritic growth. But

the results weren’t as pronounced.)

Kolb

can’t say if such neural connections could alleviate mental illness.

Schizophrenia may be associated with structural abnormalities

in the brain, but so far that’s not thought to be the case in

mood disorders like depression or bipolar disorder. Whatever

the mechanism, Kolb says, he’s persuaded that “the diet can

clearly alter brain function.”

Of

course, not everyone with a vitamin deficiency grows violent

or sinks into a clinical depression. So why might a

nutritional supplement help only some people? Kaplan has a

possible explanation: Some of us have “inborn errors of

metabolism.” We are born with unusual nutritional requirements

that can affect our mental function. Mental illness appears to

be partly heritable (bipolar disorder, for one, runs in

families), yet no one has discovered a gene for the disease.

Perhaps, Kaplan speculates, what’s passed down is a gene that

affects the metabolic pathways influenced by various

nutrients. Some people may simply inherit a metabolism that

demands higher-than-normal amounts of vitamins and minerals.

“What’s optimal for me may not be optimal for someone with a

mental illness,” Kaplan said at a meeting of the American

Psychiatric Association in 2003. “I’ve been blessed with a

stable mood, and I could probably eat a terrible diet and not

have any problems. Others may need additional

supplementation.”

The

next research step should be a controlled randomized trial of

how bipolar patients taking supplements fare compared with

those taking a placebo. Such studies are the gold standard for

testing drugs and supplements. But Kaplan and Popper’s efforts

have been stalled by controversy. The two scientists have been

under attack by a group led by Terry Polevoy, a dermatologist

in Kitchener,

Ontario, who

runs a Web site called HealthWatcher.net. A onetime devotee of

holistic therapies, Polevoy now crusades against alternative

treatments he considers scams. For the past four years, he and

his colleagues have accused Stephan and Hardy of irresponsibly

marketing an unproven remedy. The employees that take the

company’s orders have no medical training, Polevoy points out,

yet they’re told to encourage customers, many of them mentally

ill, to stop using traditional medicines and rely exclusively

on the supplement. “People have been injured by taking this

stuff,” Polevoy says. In one well-publicized case, a

schizophrenic man quit his medications in order to take the

supplement and wound up psychotic, in jail, and facing assault

charges.

Hardy

and Stephan, in turn, accuse Polevoy of being a front man for

the pharmaceutical industry, a charge Polevoy denies. “I may

go to a few meetings a year hosted by pharmaceutical

companies,” Polevoy says, “but I’m not paid.”

After

Kaplan and Popper published accounts of their experiences with

the formula, Polevoy charged the scientists with conducting

experimental research on patients without proper institutional

review. The allegations triggered lengthy investigations by

the scientists’ academic institutions, as well as by Canadian

and U.S.

health authorities. Kaplan and Popper were ultimately cleared

of any improprieties, but the ordeal left both so gun shy that

they stopped talking publicly about the supplement. (Kaplan

declined to be interviewed for this story. Neither she nor any

of the other scientists mentioned in this story have any

financial ties to the supplement.)

Both

scientists have had a tough time securing government support

for their psychiatric research. EMPowerplus has yet to be

approved for sale in Canada, and

Health Canada, the

agency that regulates food and drugs in that country, has sued

Truehope for advertising the product to Canadians who might

wish to import it. “The manufacturer has not provided us with

scientific evidence that the drug is safe and effective,” says

Jirina Vlk, a spokeswoman for the agency. Hardy and Stephan,

in turn, have sued Health Canada for

blocking shipments at the border. Health Canada

initially denied Kaplan permission to pursue a randomized

study of the supplement in 100 bipolar patients, although

Kaplan already had funding from the Alberta

government. That decision was reversed in 2004, after the

agency established a new division dedicated to overseeing

supplements and natural health products.

Meanwhile

in the United

States,

Popper and Kaplan recently secured approval from the Food and

Drug Administration to conduct an even larger clinical study

of the supplement. Other scientists think this is long

overdue. “It’s something that needs to be investigated,” says

L. Eugene Arnold, a psychiatrist at Ohio

State

University who

plans to explore the use of zinc to treat ADHD. “There’s no

point in people arguing about whether it works or not without

getting some data to get the answer.” Arnold is no

advocate of alternative treatments for mood disorders, but he

thinks it’s reasonable to suspect that vitamins and minerals

might have an effect. The standard treatment for bipolar

disorder is lithium, he points out. “And what is that but a

mineral?”

For

Hardy and Stephan, the long wait for scientific validation has

been frustrating. But they are patient. “It’s like any new

discovery—acceptance is slow to come,” Stephan says. “But that

will change. It will come.”